Table Of Content

“True Peak” (TP), also known as “Intersample Peaks” (ISP), is a technical reality which is still not fully understood in today’s music production world. With the rise of streaming platforms using Loudness Normalization, and the widespread adoption of home‑studio workflows, True Peak notion have re‑emerged—despite having existed since the earliest days of digital audio distribution with the advent of the Compact Disc in 1982.

In the music production and recording environment, True Peak matters only at the Mastering stage, when a “digital audio” file is finalized before distribution.

What Is “True Peak”?

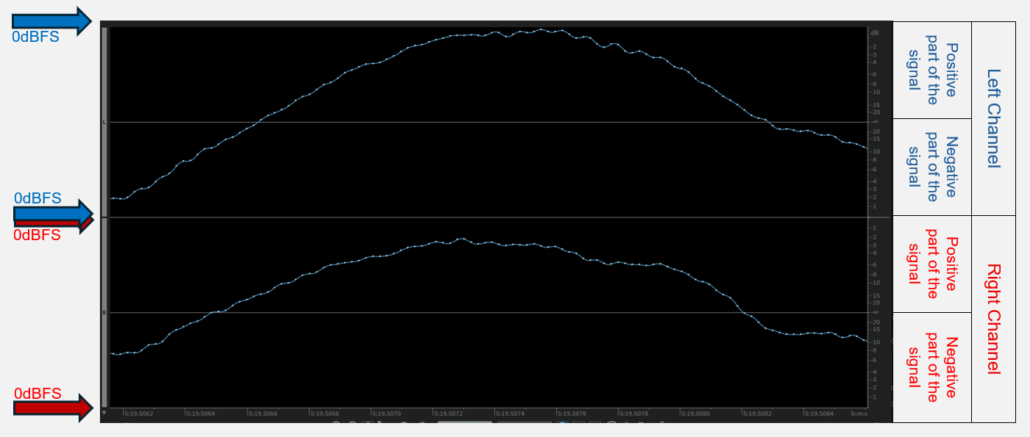

In a digital audio file, True Peak refers to the representation of continuous levels when they exceed the value of neighboring samples. It represents a real analog level that can exceed the level suggested by two successive samples, during conversion from digital domain to analog (Figure 1).

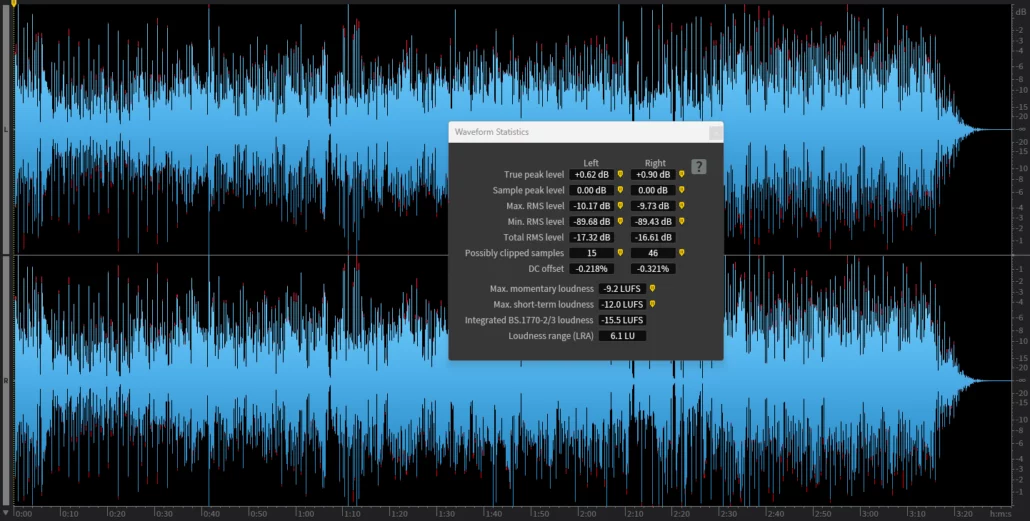

Figure 1: Analysis of a digital audio file. On the selection: in yellow, the True Peak (TP) levels created by two consecutive samples whose values are close to the digital maximum (Full Scale / 0 dBFS). Across the entire audio track: on the left channel (top), the TP level reaches +0.77 dBFS; on the right channel (bottom), the TP level reaches +0.60 dBFS. The software indicates 17 TP events on the left channel and 14 TP events on the right channel. In light grey: additional True Peak levels can be observed but remain within Full Scale. (Software: iZotope RX).

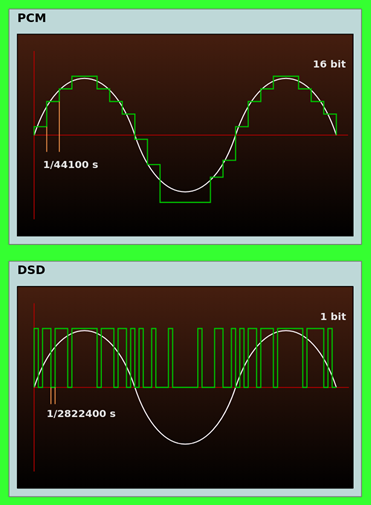

True Peak is a concept specific to LPCM encoding, which is widely used in music production through digital tools that allow audio engineers to record, edit, and create sound. The same digital audio “language” is also ubiquitous on the consumer side, as it underlies virtually all forms of digital playback — from streamed music to CD-Audio and any other digital format stored or distributed today.

At this stage, it is also worth remembering that there is a second type of digital audio encoding: the DSD (Direct Stream Digital). For it, the notion of True Peak is inapplicable. We will explain why at the end of the article in a dedicated chapter.

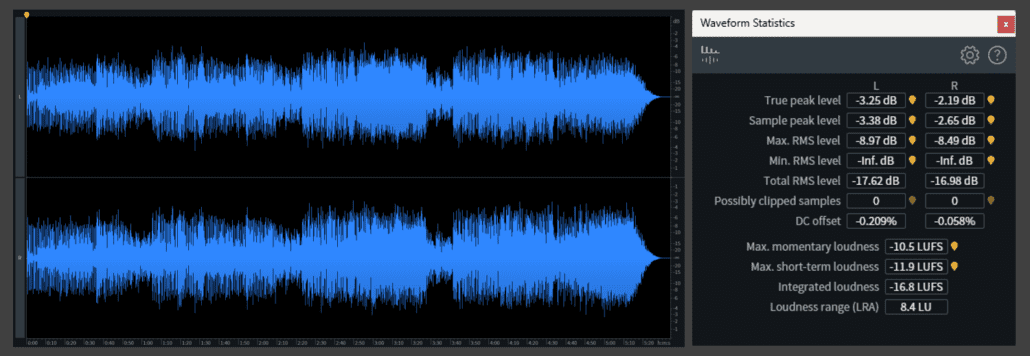

True Peak values do not indicate the “overall level” of a recorded audio file. Other measurements representing an average level are more useful to identify the perceived level of a recording. These include RMS, and another measurement based on a more advanced method: Integrated Loudness (Figure 1: Integrated BS.1770 Loudness).

The term « RMS » (Figure 1: Total RMS level) indicates the arithmetic mean defined by the waveform represented in LPCM encoding. This value therefore represents, in a sense, the “average” of the recorded signal. It is expressed in the common digital scale, in Full Scale decibels (dBFS)—a negative scale whose maximum value is fixed at “0”.

Today, studios use a more recent calculation method that refines the idea behind RMS through a similar digital scale: LUFS (Loudness Units relative to Full Scale). Its algorithm is more elaborate, taking into account how the human ear behaves as a function of frequency and perceived intensity (equal-loudness contours; Fletcher & Munson, 1933). Consequently, for a given piece of music, the measurement used to define the perceived “average” level is Integrated Loudness, not RMS—let alone True Peak maximum values, which can provide no meaningful indication of overall recorded level.

In the digital audio domain, True Peak concerns any multichannel LPCM file intended to be played through a sound reproduction system. Today, it has resurfaced in studios largely due to the development of streaming platforms and the “recommendations” they provide to mastering studios. However, the phenomenon itself has remained unchanged since the invention of LPCM and applies to any file meant to be played back, including CD-Audio.

In the case of stereo music with two channels (left and right), there is a dual stream of digital data representing two separate waveforms. This dual digital stream is converted into two separate electrical signals, sent to a pair of loudspeakers. Depending on the performance of the reproduction system, playback will be more or less faithful. As a result, what we perceive through a given playback system can vary greatly in reproduction quality compared to the original file as created by the artist, producer, and audio engineer.

Beyond obvious criteria such as frequency response, dynamics, or spatial precision (which depend strongly on the entire playback chain), True Peak can cause issues at the very first link in the chain. It can also suggest other problems when the file is transformed.

The downsides of True Peak

When True Peak values exceed certain thresholds—and depending on the use case—the consequences can become problematic during the use of the audio file.

As discussed, True Peak levels do not describe loudness; they only reveal a possible and real continuity of the analog signal during playback. However, it can happen that the analog level reconstructed between two successive samples exceeds the maximum numerical value (Full Scale).

DAC overload

Understanding True Peak matters because it can cause negative consequences during playback when music comes from a digital format. Today, before releasing masters, True Peak values are evaluated and sometimes controlled by mastering engineers. When finalizing the last digital processing steps on the mixes they receive, mastering engineers can adjust these “digital-to-analog” transition levels to avoid audible distortion that could appear on consumer playback systems.

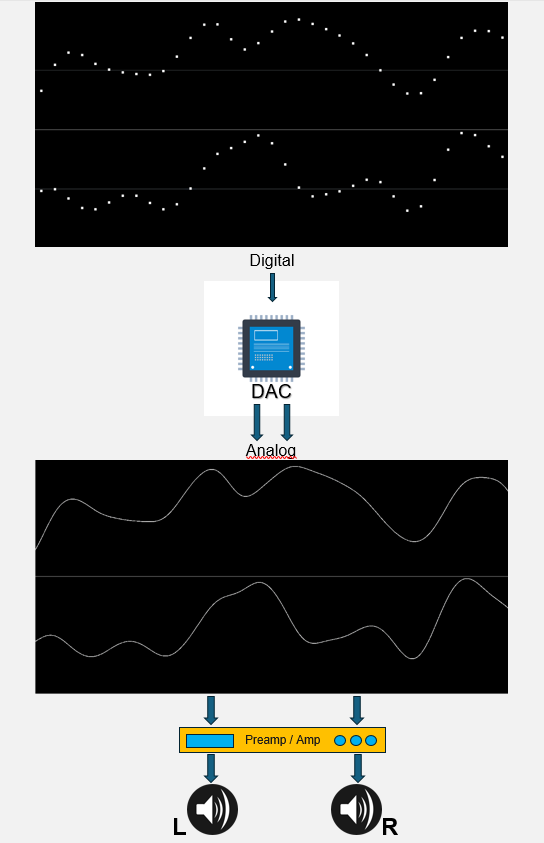

In any recorded audio file, all samples are legitimate because they are, by definition, located within the digital scale. They exist in the positive part of the signal and the negative part, below 0 dB Full Scale on both sides of the waveform (Figure 2):

Figure 2: Stereo representation of two digitized waveforms corresponding to the left and right channels.

To be heard through transducers (loudspeakers or headphones), every digital audio signal undergoes digital-to-analog conversion at playback. The complex electronic circuit responsible for this domain change is a DAC (Digital-to-Analog Converter). A DAC converts discrete sample values into a continuous electrical current. Further down the chain, this current is amplified before being sent to a loudspeaker system. Transducers convert electrical current into mechanical energy, which explains the movement of the loudspeaker cone and thus the perception of sound (Figure 3).

Figure 3: The LPCM digital audio signal is sent to the DAC to be converted into an analog electrical signal, which by definition is continuous. This signal is then amplified before being transmitted to the loudspeakers.

Inside the DAC, if the reconstructed analog representation exceeds the level corresponding to the digital maximum (0 dBFS), on the positive or negative side, the DAC is asked to reproduce an analog level whose digital equivalent does not exist. As a result, the DAC clips at that point. In practice, a form of momentary distortion is created: sample values are converted according to the DAC’s capabilities and performance, but the analog signal necessarily contains conversion errors because True Peak values cross the digital limit. This distortion is usually not intentional and is not, in principle, part of what the artist, producer, or engineer intended for the master.

Hence, in theory, the importance of creating masters with controlled True Peak values so that DACs can translate continuous levels without introducing this kind of distortion.

In practice, the overall quality of playback systems plays a fundamental role in transparent reproduction, because the best systems generate as little distortion as possible. Regarding the management of excessive True Peak values, the sensitive link is the DAC’s performance. With low-end DACs, the distortion caused by these values is the most audible; conversely, on high-end professional or audiophile systems, the distortion becomes inaudible thanks to much more capable DACs.

Today, some of the highest-performing DACs on the market are those using DSD technology, implementing a coding method called Delta-Sigma (sometimes referred to as Sigma-Delta). The DSD standard was introduced to the public in 1999 with the Super Audio CD (SACD).

SACD: Unlike LPCM, which has defined digital audio worldwide across virtually all applications from the CD’s release in 1982 to today, SACD (Super Audio CD), created in 1999, relies on a different digital language: DSD.

DSD in high-end DACs. Found in many modern high-performance DACs, DSD is indifferent to the notion of True Peak in part thanks to the internal Delta-Sigma process—a specific technology for calculating samples when converting incoming LPCM information inside the DAC.

DACs are never all the same: their electronic design can vary greatly between models. The best converters are built with optimal-quality components (more expensive), sometimes individually selected and matched. There are also multiple engineering approaches, depending on technologies, design choices, and component costs.

To give a sense of the market in hi-fi, I compiled a non-exhaustive list by browsing retail sites. You can find external DACs for €15 as an entry-level price (a). Fortunately, more advanced DACs exist for a few hundred euros (for example under €200) (b). Prices can rise to several thousand euros (c and d)—for this “single” function: converting two digital audio signals (left and right) into two corresponding analog signals in real time.

a. Entry-level portable DAC, Jade Audio JA11, source Son-Video.com

b. Standard DAC, Topping Audio DX3Pro+, source Topping Audio

c. Audiophile DAC, Atoll DAC300, source cta-hifi.com

d. High-end DAC, McIntosh MDA200, source Elecson

It goes without saying that the quality of digital playback is entirely dependent on the quality of the DAC used—just as it depends on the amplifier and speakers. The DAC is a crucial element that is generally underestimated by the general public. I challenge you to run comparisons if you ever have the opportunity.

In short: during playback of digital files, True Peak management happens only inside the DAC. The DAC’s quality is decisive in its ability to handle True Peak values when they exceed the top of the digital scale.

Lossy codecs

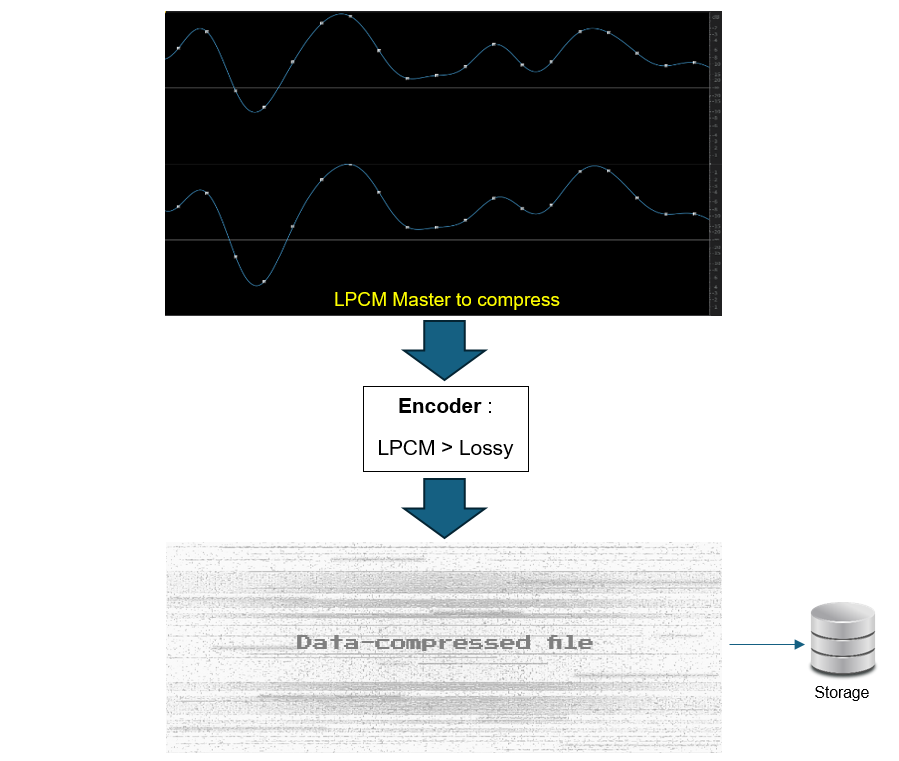

In general, an audio codec is an algorithmic system that works in two parts: an encoder and a decoder. In this article, we will focus only on lossy codecs—those that, during encoding, discard audible information in exchange for a file size of only a few megabytes. By contrast, so-called lossless codecs reproduce the same signal after decompression, meaning True Peak values remain the same; therefore, there is no reason to focus on lossless transformations here.

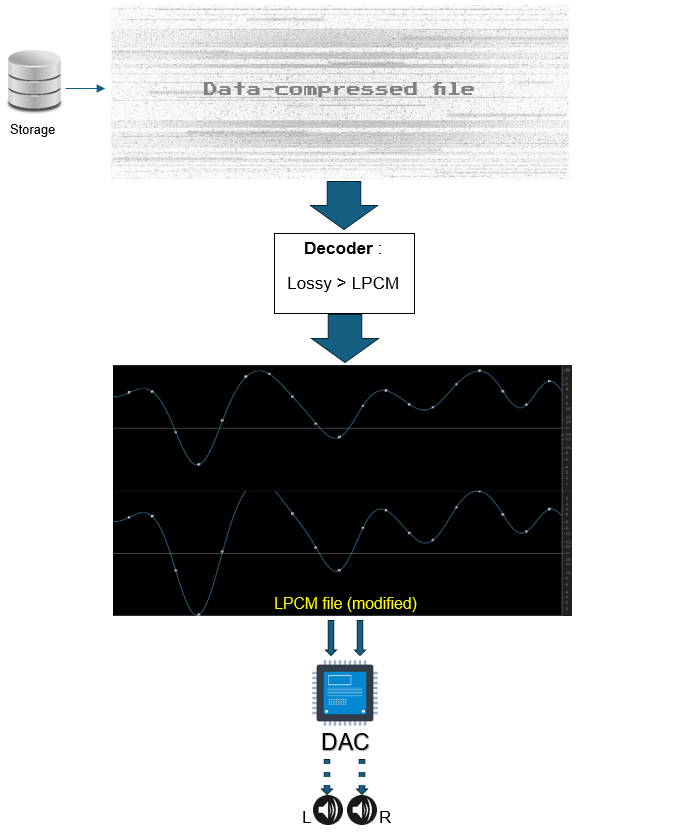

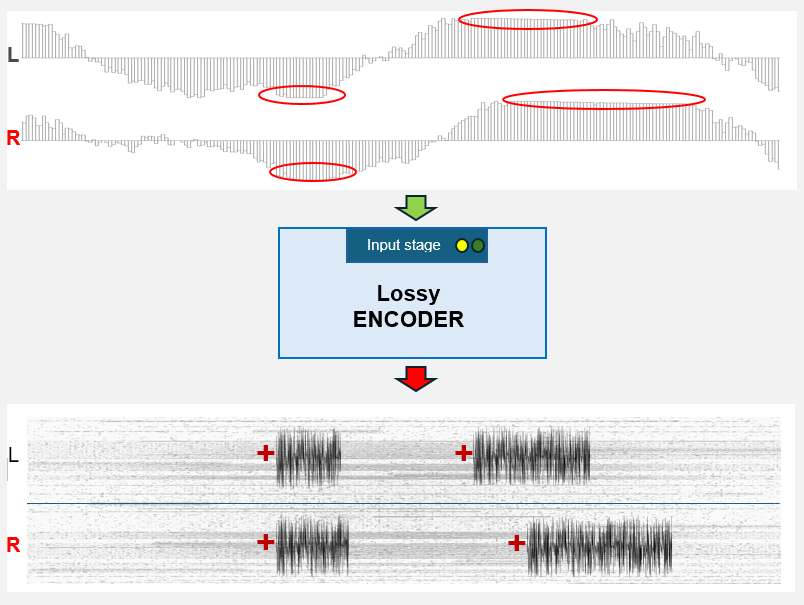

We therefore transform the original master signal, encoded in LPCM, into a new signal via “lossy” data compression. That is the principle of encoding. LPCM files from mastering studios (.wav, .aiff) can be encoded at any time into other formats to reduce their size, as in mp3, AAC, Ogg Vorbis, etc… The new file is then stored (Figure 4). Only at playback does the decoder decompress the small file so it can be reproduced by a listening system—specifically through the DAC (Figure 5).

Figure 4: Creation of a lossy file from a master file (LPCM). “Lossy” refers to a format that undergoes a loss of audible information compared with the raw LPCM master format. The encoder stage of the algorithm produces this “compressed” file. The master undergoes “data compression.” The only advantage of the resulting file is its reduced size; the downside is that it loses sound quality due to the loss of audible data. During encoding, the higher the bitrate, the less damage it suffers. Note that lossy formats cannot be represented in the same way as LPCM in « amplitude over time ».

Figure 5: Playback of the lossy file. During playback of the compressed file, the decoder recreates new samples in LPCM—the only language that DACs can interpret as a continuous signal. The lossy file is therefore decompressed with the losses created during encoding. Once degraded, it is impossible to recover the original LPCM file because lossy encoding is irreversible. Note that in this realistic representation of the reconstructed LPCM file (the example will be studied later), one sample could not be created within the common digital scale. That sample therefore does not exist, and the continuous reconstruction produces a large True Peak value—confirming, as we will see later, that True Peak can be poorly managed during lossy decoding.

Lossy Encoding

When converting from LPCM to a lossy format (mp3, AAC, Ogg Vorbis…), overly strong signal levels can overload encoders (Figure 6). Lossy encoders need headroom to correctly convert data. If the input signal is too hot, the encoder saturates and produces its own distortion, which is then mixed into the encoded signal—something to avoid unless it is intentionally desired by the producer, artist, or engineer at the mastering stage.

Figure 6: Encoding a .wav file to a lossy format. If the input level is too high, the encoder’s input stage saturates and distortion appears, adding to the encoded signal.

However, note that the levels discussed at the encoder input are sample peak levels, not True Peaks, because the encoding process remains entirely within the digital domain.

In Mastering, the goal is to find the best “overall and final level” solution to avoid this kind of encoder distortion caused by the highest sample peaks.

Lossy Decoding

Once masters are compressed into their lossy forms, we also have to ensure that the newly created samples do not generate True Peak values that cause clipping during playback through the DAC. Indeed, because lossy encoding is destructive, the sample values necessarily change within the digital scale. These new values can induce True Peak levels (Figures 7a, 7b, 7c, and 7d).

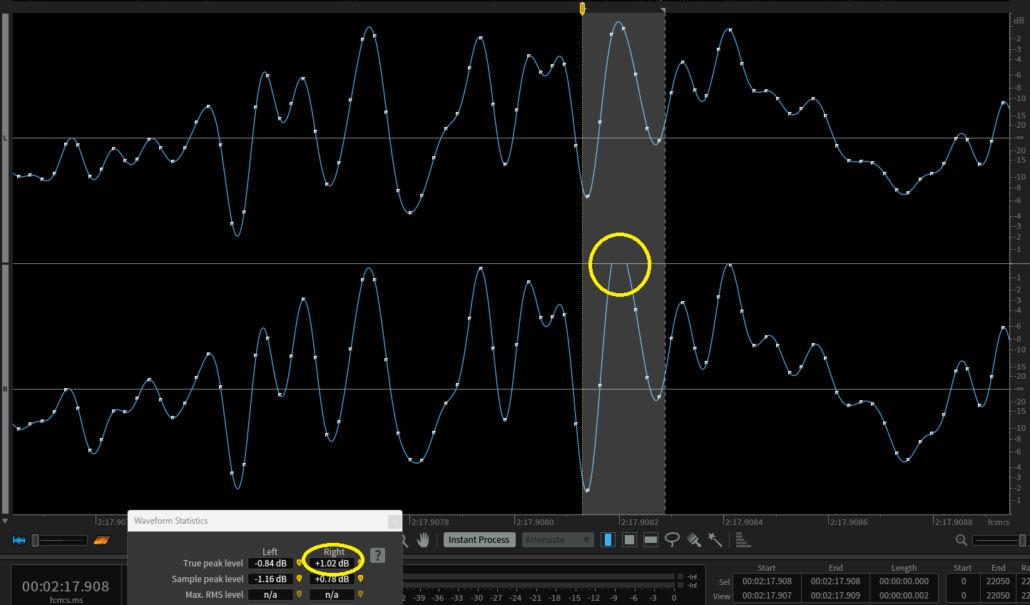

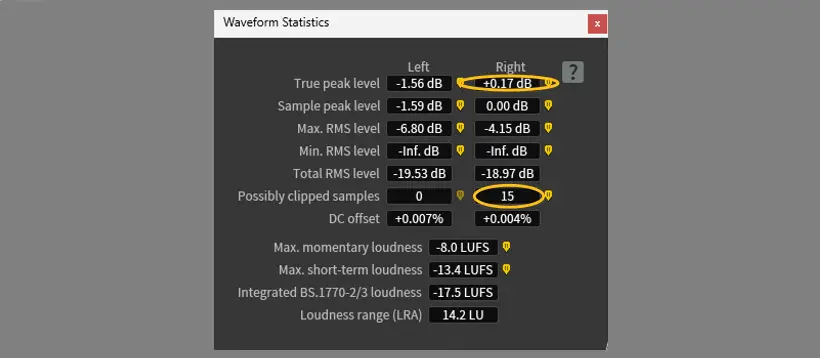

Figure 7a: In RX (iZotope), representation of a portion of an LPCM audio file from a CD (Michel Jonasz, “Joueurs de Blues”, zoomed around 2:17.908).

Figure 7b: Representation of the same portion after lossy encoding of the original file using a low bitrate (Ogg Vorbis, 64 kbps (Q=0)). Note the presence of a significant True Peak on the right channel (+1.02 dBTP), while at the same time position the left channel’s sample value has decreased. This is due to the new distribution of samples within the digital scale.

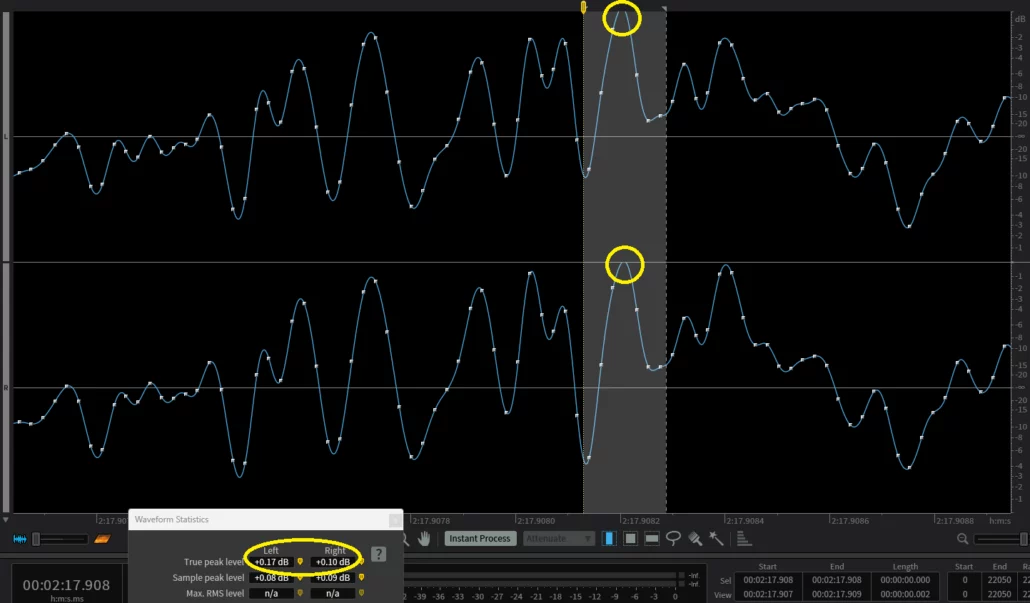

Figure 7c: Representation of the same portion after Ogg Vorbis lossy encoding at maximum quality (Q=10, i.e. ~500 kbps). Despite the very high bitrate, note the presence of moderate True Peak values on both channels (Left: +0.17 dBTP, Right: +0.10 dBTP). As above, this result is explained by the new sample distribution within the digital scale.

Note that in Figure 7c, at the True Peak location in the Left Channel, one sample is missing. In LPCM we would normally expect a sample at every digital step, but here the decoding algorithm was unable to determine a sample value within the usual scale—clearly creating that True Peak during signal reconstruction.

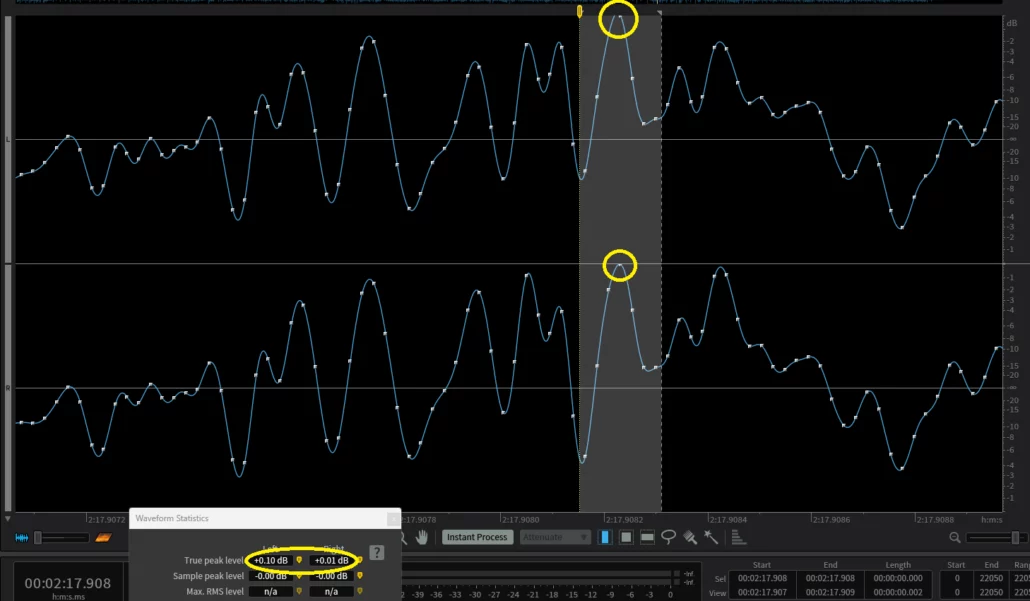

In Figure 7d, note also that in the original CD file, both concerned values are True Peaks but nearly invisible: Left: +0.10 dBTP and Right: +0.01 dBTP.

Figure 7d

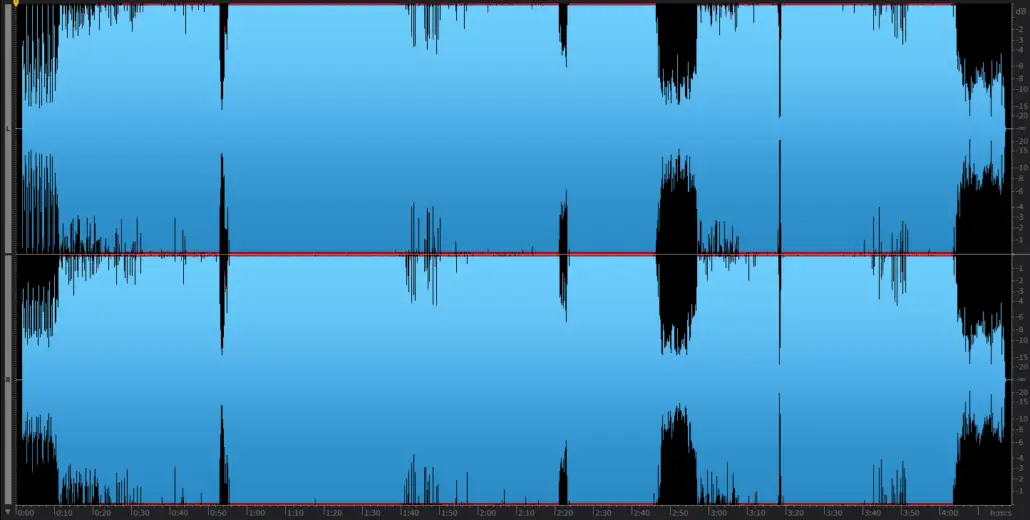

In the track concerned, analysis shows a total of 61 True Peaks exceeding the numeric maximum (15 on the left channel and 46 on the right) (Figure 7e). This is explained by the fact that at the time of this album’s CD release (the example is from the first CD edition, released in 1986), mastering engineers did not pay attention to True Peak values. Because the average loudness was relatively low (−15.5 LUFS) and dynamics were significant, these True Peak values were not problematic. By contrast, modern productions in more mainstream genres are more likely to cause True Peak interpretation issues, due to higher average levels, DAC overload, and level overload during lossy encodes.

Figure 7e: Waveform representation of the entire track “Joueurs de Blues”. Album “La nouvelle vie”, Michel Jonasz. Album released in 1981 (originaly on vinyl and cassette). The digitization of the tapes for the CD release took place between 1984 and 1985. Note the track’s dynamics (difference between low and high levels) and the occasional True Peak values reported in the analysis.

Summary of the issues caused by True Peak

True Peak values exceeding the digital maximum create interpretation problems during playback through DACs that saturate—especially with common & low-quality DACs.

True Peak also creates many issues during lossy decoding. This is due to the fact that samples are fully recalculated, thus generating new True Peak values. Those can significantly exceed initial True Peak values found on the original LPCM file. These overshoots are strongly related to the applied bitrate for the conversion. They also heavily depend on the initial file’s sample peak levels if they are too high.

Why True Peak is challenging for streaming platforms

The limits of streaming

Today, in 2025, with a subscription, most platforms offer a large part of their catalog in standard LPCM .wav quality (minimum 16-bit / 44.1 kHz, CD quality) and very often in high-resolution—sometimes exactly the same format delivered by mastering studios (.wav 24-bit at 44.1 kHz, 48 kHz, 96 kHz, etc.).

However, beyond their ability to deliver much of the catalog in high resolution, these platforms also provide a lossy format to subscribers. Depending on general public usage, subscribers often rely on lossy formats for mobile listening (e.g. smartphone) because they are less demanding in bandwidth and file size. Also, the poor quality of lossy audio is less noticeable on small playback systems, mainly due to their limited frequency response.

It is important to understand that lossy coding from studio masters (commonly .wav 24-bit minimum @44.1 kHz) is never done in Mastering. The lossy files provided by platforms are automatically encoded by the platforms themselves from the files they receive, which can cause clipping due to poor management of levels that are too hot at the encoder input, and therefore also True Peak levels that are not properly controlled.

Only mastering professionals are able to finalize masters whose encoding and decoding will not induce audible distortion due to uncontrolled levels. This is how we deliver “clean” masters in which this type of distortion cannot be added to the artifacts created by information loss during conversion to lossy formats.

Beyond streaming platforms, lossy conversions can also be performed by anyone with the right software—for example converting a .wav file into an .mp3 using Apple’s “Music” app or third-party software like VLC on Windows (Figure 8). In that case, conversion quality can be poor because the user cannot control encoder input levels to avoid overload. The user also cannot control True Peak values created during decoding.

Figure 8 : Apple Music (macOS), which replaced iTunes in 2019, and VLC (Windows) are among the most commonly used programs for users to encode LPCM audio files into lossy formats.

Recommended maximum True Peak values

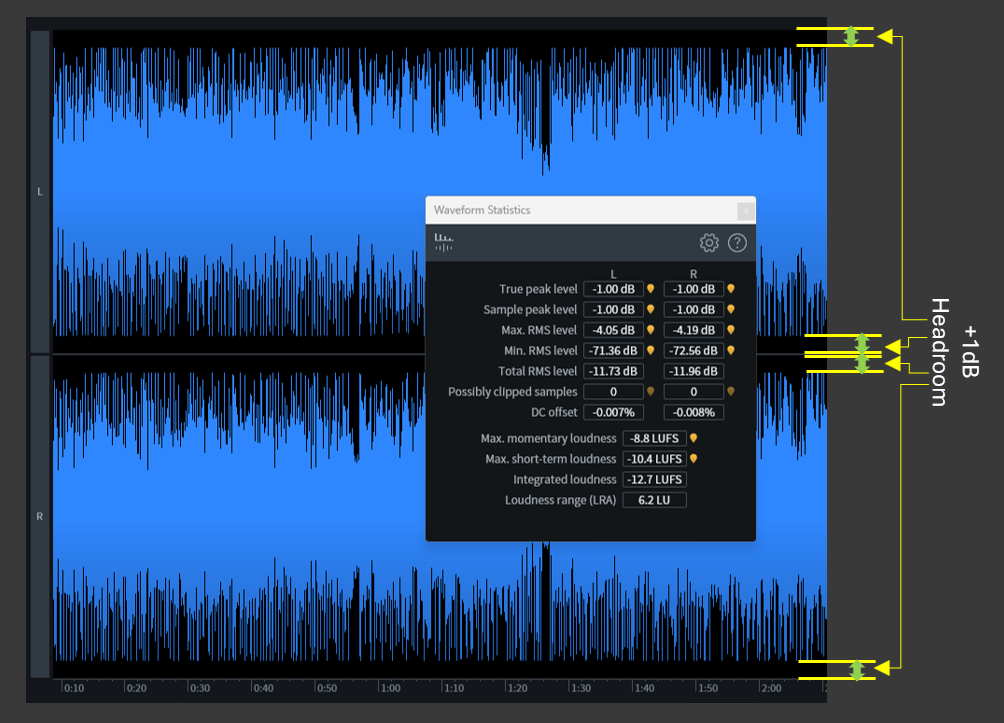

To address this True Peak problem—which worsens with lossy encoding and decoding—platforms recommend masters whose True Peak values do not exceed −1 dBFS (Figure 9). This is the same recommendation introduced in 2010 by the EBU for broadcast and TV mixing (EBU R128).

Note that Spotify recommends −2 dBTP if masters exceed the integrated loudness value of −14 LUFS. Spotify is still one of the only major streaming platforms that delivers audio in a lossy format (Ogg Vorbis, bitrate between 160 and 320 kbps depending on subscription tier). It is therefore not illogical to add an extra −1 dBTP safety margin so that their codec behaves ideally and avoids generating problematic True Peaks.

Figure 9 : Example of a master reaching a maximum True Peak of −1 dBTP in line with EBU R128. This represents 1 dB of headroom between the maximum True Peak level and the digital maximum (0 dBFS). If mastering exclusively for Spotify following their recommendation, we would need to reduce the master’s overall level by an additional 1 dB—i.e., 2 dB of headroom! …whereas if their policy shifted toward a fully lossless catalog, we would not need to reduce this level and music quality would finally be fully legitimate.

By contrast, unlike the Broadcast Sector—where maximum True Peak limits are strictly enforced—the Music Industry operates without any mandatory rules. No organization or platform will reject a master solely because its True Peak level is too high. The term “recommendations” should therefore be understood in its strict sense: guidelines that, depending on context or musical genre, are not always followed.

True Peak across musical genres

Today, certain musical genres are mastered at consistently very high and competitive average levels, a practice inherited from the so-called “Loudness War” that emerged in the early 2000s. By contrast, other genres have always been mastered with greater depth, preserving the natural dynamic range of the recordings. As a result, the management of maximum True Peak values varies accordingly.

The case of dynamic music

Unlike the broadcast domain where maximum levels are actually applied, there are no rules or obligations in the music industry. No organization or system will reject a master because its True Peak level is too high. In music production, these are only “recommendations” in the strict sense, and they are not always followed.

Occasional True Peak values of small amplitude (e.g., 3 or 4 TP values at +0.3 dBFS in an entire track) generally cause no difficulty, because the distortion created during DAC reconstruction is either very small or extremely brief, and therefore unnoticed. Some albums may have only 1 or 2 tracks out of 10+ where True Peaks can be annoying, especially when played through common, non-performant DACs.

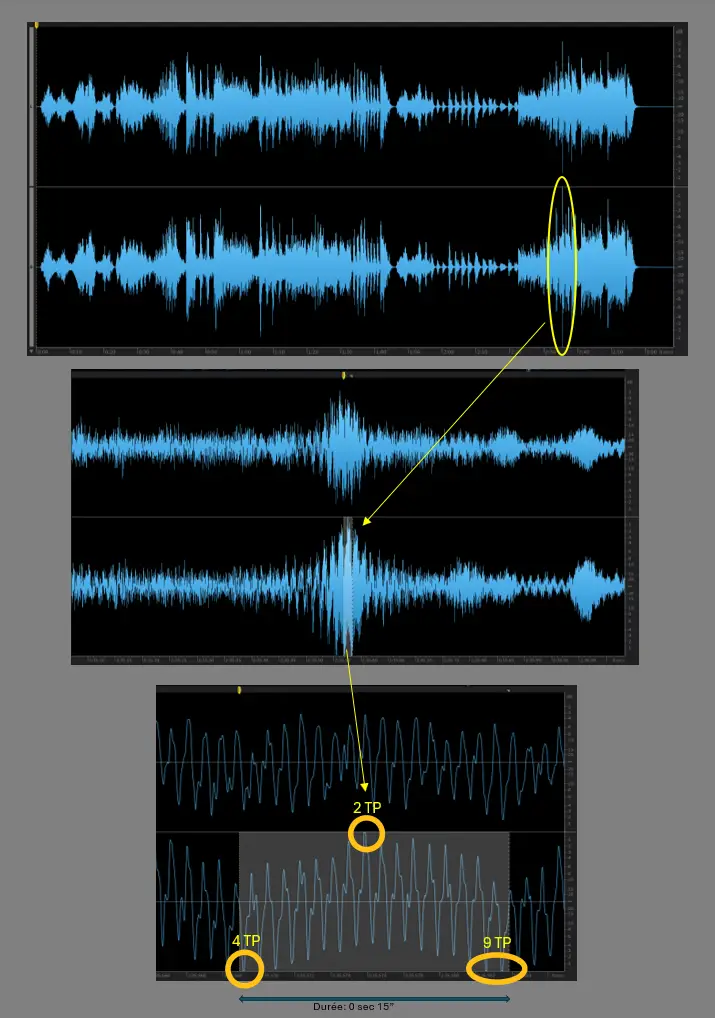

In the following classical example (Figures 10 & 11), we observe 15 True Peak values on the right channel concentrated between 2:35.569 and 2:35.584—a time interval of only 0.15 seconds. At that point, depending on DAC quality, the ear might perceive a general distortion affecting all 15 TP values at once.

On the very successful 18-track album from which this excerpt is taken, only two tracks present True Peak issues exceeding Full Scale. These overshoots were apparently not considered during mastering.

Figures 10 & 11 : Vivaldi Concerto l’Inverno n.4 Allegro – Le Quattro Stagioni – Interpreti Veneziani (Cd-Audio, In Venice Sound, 2013).

The Loudness War as a starting point

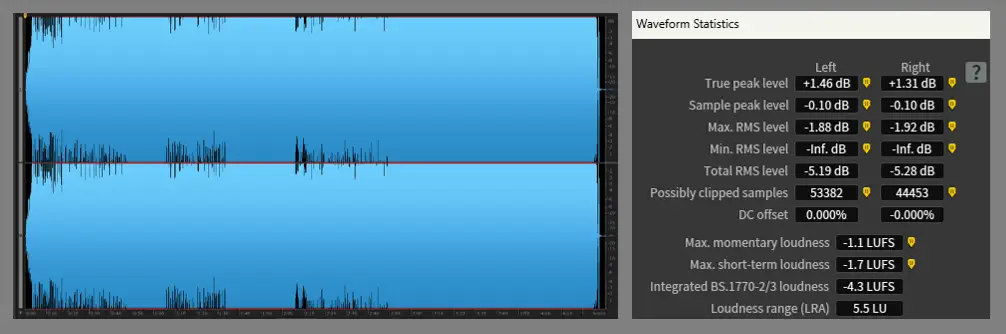

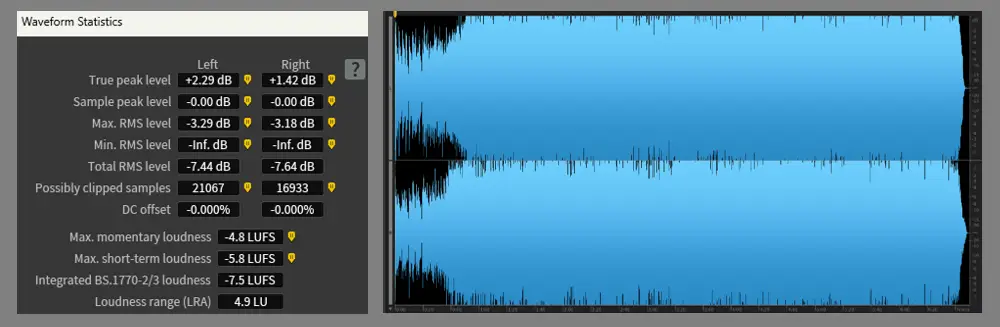

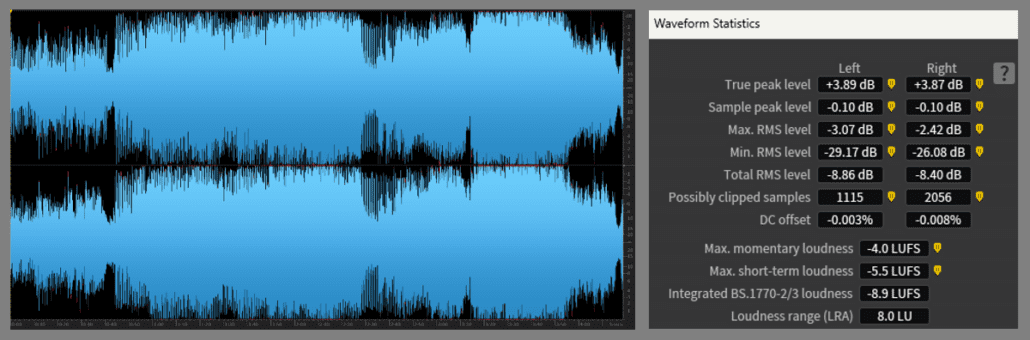

Today, it is not rare for music productions to be mastered without taking True Peak into account, or with a high presence of True Peaks exceeding 0 dBFS. The “Loudness War”, which peaked in the 2000s, predates the widespread availability of tools to control these peaks in studios. The consequences were negative: studios worldwide pushed technology to maximize signal amplitude in the file, generating very large True Peak values (Figures 12, 13 and 14):

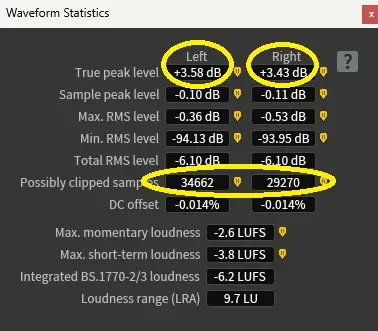

Figure 12 : Analysis of Red Hot Chili Peppers’ “Parallel Universe” (Album Californication, Warner, 1999)

Figure 13 : Analysis of Iron Maiden’s “Ghost of the Navigator” (Album Brave New World, EMI, 2000)

Figure 14 : Analysis of Madonna’s “Let It Will Be” (Album Confessions on a Dance Floor, Warner Bros, 2005)

The legacy of the Loudness War: mainstream codes becoming established

While the last 15 years have generally moved toward more dynamic productions, certain genres are still produced very loud even with Loudness Normalization. Digital technology keeps evolving, and loudness values can still exceed those of 20 years ago depending on artists.

The biggest issue with hot levels isn’t volume — it’s the distortion they bring.

Dave Collins, Mastering Engineer

Source : « Production Masters Podcast » interview with Dave Collins, 30 april 2018, Tape Op Magazine.

The problem with the loudness war is distortion. When you push levels beyond what the medium can handle, distortion is the result. (...) The clipped sound has become part of the signature of modern mastering — not because it is better, but because people have become accustomed to it.

Bob Katz, Mastering Engineer

Source: Mastering Audio: The Art and the Science, 3rd edition (Focal Press), chapters on the « Loudness War » and « Digital Clipping ». In his book, the author argues that distortion remains the primary cause of the Loudness War phenomenon—namely, excessively high average levels. He also points out that contemporary generations have become accustomed to distortion, which may help explain certain artistic intentions.

The Loudness War has had creative consequences: its first decade of influence established “codes” within genres. Distortion generated in productions sometimes becomes part of an artistic legacy. Many mainstream artists aim for impact using multiple forms of distortion, including distortion produced by True Peak values affecting playback. Producers in Pop, Electronic, Urban, or Rock music often argue that loudness must reflect its time and that distortion can be part of art as an expressive tool (Figure 15).

Figure 15 : Analysis of Skrillex’s “Ragga Bomb” (Album Recess, Owsla/Big Beat Records, 2014). In this example—as in still today’s many Pop productions—there are 56,012 True Peaks on the left channel alone; the highest reaches +3.58 dB, which is enormous. Here, the choice seems to be entirely intentional.

Clipping is just another sound. Whether it’s appropriate depends entirely on the musical context.

Dave Collins, Mastering Engineer

Source: Gearspace.com Q&A thread with Dave Collins (public thread, June 17, 2010).

In some genres, distortion is fully intentional. True Peak-related distortion is one example among others created with common studio tools: harmonic generators (exciters), certain EQ types, compressors, limiters, etc. This sonic research—used to reach a louder and more competitive level—may seem excessive, but if intentional it remains legitimate. It is therefore the responsibility of the sound professionals to deliver music where such distortions are controlled and serve clearly defined intentions.

If an artist wants intensity, sometimes harmonics and saturation are part of achieving that.

Maor Appelbaum, Mastering Engineer

Source: Maor Appelbaum Masterclass – Pensado’s Place (guest episode).

Some styles need to sound dirty, gritty, saturated — that’s the vibe, that’s the art.

Maor Appelbaum, Mastering Engineer

Source: SonicScoop interview, “Inside the Mastering Mind: Maor Appelbaum”.

If the mastering is excellent, the sole fact that it exceeds “recommended True Peak values” is clearly not enough to question its quality. As we will see, limiting True Peak values can itself have audible consequences. Ultimately everything depends on the initial intentions and on how the mastering engineer executes decisions in the sound.

True Peak ignored in Integrated Loudness

In the 2010s, Loudness Normalization was implemented with the growth of streaming. It followed the EBU’s momentum from 2010 to standardize broadcast program levels. Similarly, streaming platforms aimed to reduce level differences within playlists, because music has never been mastered to a single loudness standard. To improve listening comfort, loud tracks are turned down, and all tracks end up played at roughly the same perceived level—regardless of ISP values even if they exceed 0 dBFS.

Moreover, this practice intended to end the Loudness War: the louder the Integrated Loudness, the more gain reduction is applied to reach a platform’s target. This discourages excessive loudness.

However, True Peak is completely ignored in Integrated Loudness calculation: the ITU loudness algorithm does not include ISP. As a result, loudness normalization does not account for True Peak. In mastering, controlling True Peak does not affect how much a platform will turn down a track. Nonetheless, because excessive True Peaks can generate distortion on consumer playback systems, perceived loudness is impacted in practice: adding distortion to a signal necessarily increases perceived loudness, even if the Integrated Loudness algorithm ignores it.

Managing True Peak

At the end of the mastering process, one key concern is to check maximum True Peak values across all masters: the highest value reached and how frequently these peaks occur. Through listening and dedicated digital tools, we can evaluate their annoyance both in DAC playback (clipping) and across lossy transformations (encoding and decoding).

Detecting “True Peak Max” in mastering

When finalizing masters for a client, we pay close attention to TP Max values for the two reasons above: ensuring proper behavior during lossy compression/decompression and avoiding distortion caused by excessive digital levels.

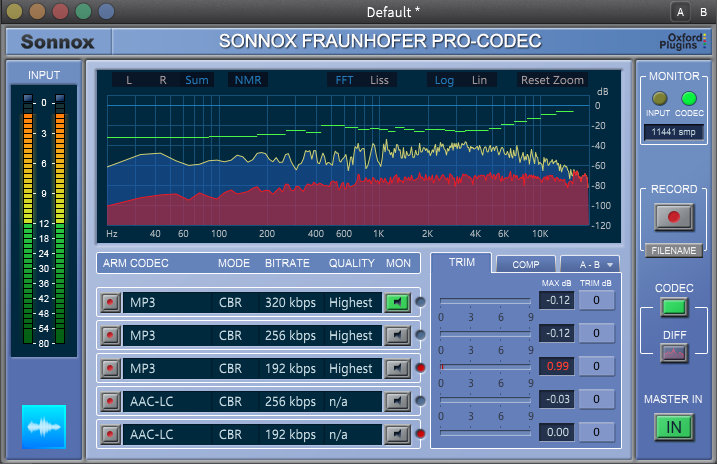

Professional tools exist to adjust encoder input level depending on codec and bitrate. Not all codecs behave the same: for the same overload, some generate less distortion than others, and results also depend heavily on bitrate. The higher the bitrate, the less degradation occurs and the less distortion emerges during overload. Examples include the excellent Fraunhofer Pro-Codec (Sonnox) (Figure 16), as well as Apple’s tools through the Apple Digital Masters program.

Figure 16 : The “Fraunhofer Pro Codec” plugin (Sonnox), analyzing in real time different encoding/decoding streams depending on chosen codecs and bitrates (here: mp3 @320 kbps, 256 kbps, 192 kbps and AAC @256 kbps and 192 kbps). The analysis shows that the master would clip the mp3 codec at +0.99 dBTP if a 192 kbps bitrate were used. In the other examples, the codec generates no problematic True Peak.

Why True Peak is not always a mere formality today

Mastering aims to enhance the artistic message and make the project coherent and competitive. It also aims to deliver masters that translate well across all ranges of playback systems, from everyday consumer systems to the most advanced ones. Mastering studios ensure this, among other things, through control of True Peak levels. The expertise of mastering engineers relies on real signal-processing work to improve what is entrusted to them.

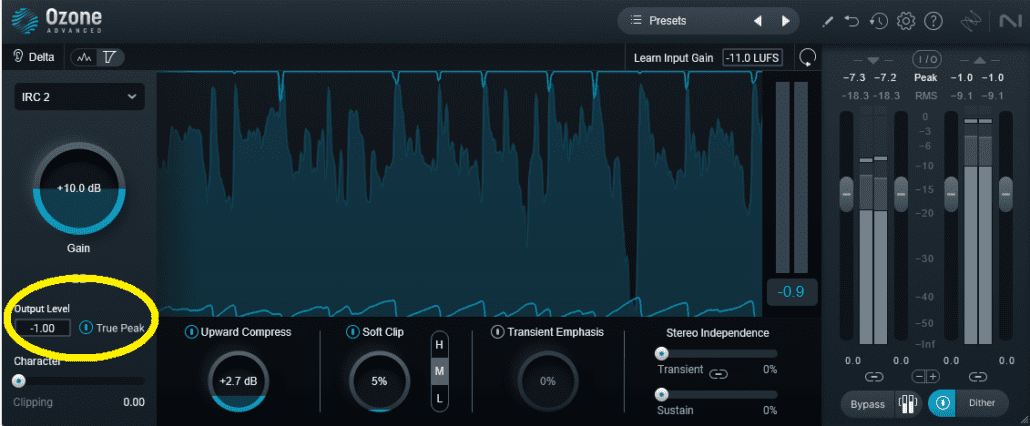

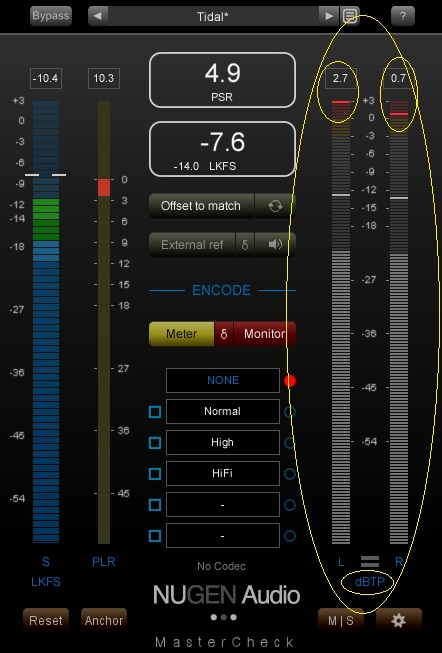

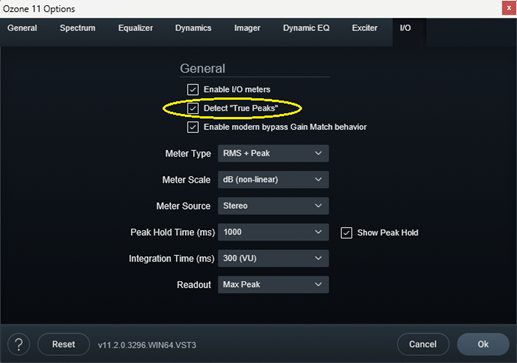

Today, all major audio software can display maximum True Peak levels. If we consider it important to create −1 dBTP headroom, we use brickwall limiters equipped with True Peak detection (Figures 17, 18 and 19). When enabled, the limiter detects all levels (sample peaks and ISP) and reduces the signal accordingly whenever it exceeds a user-defined threshold. This helps guarantee a signal free of TP levels that would be problematic during DAC conversion.

However, enabling True Peak mode is not always without side effects. With TP mode engaged, some limiters color the signal, while others are far more transparent. Yet coloration can be desirable depending on artistic intent. Professional mastering is always intention-driven, and processing choices are based on the signal’s characteristics. If True Peak limiting reduces quality or richness, we look for alternatives: different limiters or other tools better suited to the signal. We can also ignore True Peak limiting and adjust levels while monitoring with dedicated True Peak meters (Figures 20 and 21).

Figure 17: “Invisible Limiter G3” (A.O.M) controlling True Peak levels in the limiter section so no True Peak exceeds the user-defined value. Here, threshold is −1.00 dB(FS). With “True Peak Aware” enabled, no ISP exceeds −1 dBFS, so the maximum level is −1 dBTP.

Figure 18: Ozone (iZotope) brickwall limiter with input gain at +10 dB. True Peak mode enabled. Output level set to −1.00 dB, meaning True Peak max reaches −1.00 dBTP at the output.

Figure 19 : TDR “Limiter 6 GE” with the same configuration: gain +10 dB, threshold −1 dB, set to True Peak detection (not just “PCM/LPCM”). The meter reads a maximum of −1.0 dBTP.

Figure 20: True Peak meter example: Mastercheck (Nugen Audio). This tool does not process audio; it only displays levels.

Figure 21: Ozone True Peak meter configuration. If True Peak is unchecked, the meter reads only actual sample values without ISP interpretation.

For a given signal, one of these plugins may not display exactly the same ISP measurement as another. Differences come mainly from oversampling implementations and filtering characteristics, as well as from ITU measurement program updates. True Peak calculation is based on oversampling and smoothing filters described by the ITU in the latest version from November 2023: ITU-R BS.1770-5. However, the ISP calculation method has not evolved since version 3 of the document (August 2012): ITU-R BS.1770-3.

The Specific Case of Automated Mastering Services

As discussed in the blog article “ The Art of Mastering: Beyond the Algorithm ”, automated mastering relies on so-called “turnkey” systems designed to master any piece of music automatically, quickly, and at low cost. Two major players currently dominate this market: LANDR and eMastered.

In practice, these applications rely on artificial intelligence to deliver a mastered version of a track within seconds, without any human intervention nor artistic decision-making.

When it comes to True Peak levels, automated mastering services can apply a technically compliant maximum value, sometimes allowing the user to select a target ceiling. However, no genuine sonic evaluation is possible through this approach, as the user has no control over the processing tools used to manage these levels.

As a result, these services do not allow the listener to assess the audible consequences of True Peak limiting. This stands in contrast to the tools commonly used in professional mastering, which make it possible to hear and evaluate whether True Peak limiting has a perceptible impact on the sound.

True Peak “before”: from irrelevant to problematic

Although True Peak control is now common practice in professional mastering, this was not the case before the 2010s: we did not have sufficient tools to measure and control it precisely. Personally, I also believe Loudness War habits slowed down a willingness to question the audible consequences of True Peak.

With the arrival of CD-Audio (1982), recorded peak levels were far below those used in the late 1990s (Figure 22). At that time, nobody worried about ISP values. Generally, on CDs produced between 1982 and 1990, peak levels were several dB below Full Scale, making DAC overload impossible. The 1980s/1990s are often referred to as the “golden age of CD”. True Peak existed in theory, but its consequences emerged about 15 years later with the Loudness War.

Figure 22 : Analysis of “Rosanna” by Toto. Original, non-remastered CD version of the song (Album « Toto IV », Columbia Records, 1982). The highest True Peaks do not exceed −2.19 dBFS, leaving significant headroom. This prevents DAC overload and also allows higher quality lossy encoding/decoding.

The technology paradox

Today, because of easy mobile access—especially via connected smartphones—music consumption has deteriorated significantly. In an object only slightly larger than a hand, the entire audio system is contained: digital player, DAC, amplification, and speaker(s). This system is minimized to reduce production cost, meaning the DAC and speakers are necessarily of poor performance. Unless the smartphone is used only as a player and routed into a decent external DAC, mobile technology cannot reproduce music with high quality. In those conditions, we cannot truly appreciate the work of the artist and the technical team: microphone capture, the mixer’s work, and mastering decisions.

Even if the recording is excellent and the master is played in LPCM as produced, small systems still deliver music stripped of its qualities—qualities that are fully present in the master: extended frequency response, dynamics, detail, and the sense of space that the brain recreates when listening through a proper setup.

On a smartphone, frequency response and dynamics are restricted by the low-performance DAC, low-performance amplifier, and small speaker size. Moreover, when using the phone speaker, spatial perception disappears entirely because the listener does not benefit from the stereo effect of two speakers. In production, music is almost always built with at least a stereo dependency.

Not only can uncontrolled True Peak levels harm playback on small systems, but in those same conditions we are also fundamentally unable to hear the music as it was created and approved, according to the artists’ and engineers’ intentions.

It is clear that hi-fi systems are far less used today than in the CD era, and high-performance systems are often inaccessible for most people. Yet technological progress is real: today we can build better DACs, amplifiers and loudspeakers than ever. What should we think about the future of music consumption when Mark Zuckerberg, CEO of Meta, predicts the near disappearance of smartphones in favor of glasses providing similar functions?

Given these considerations, DAC quality remains an unchanging criterion because digital audio must be heard through it. Therefore, the topic of True Peak will remain relevant for everyday listeners unless habits and listening means evolve.

True Peak in mastering: conclusion

This real reconstruction phenomenon should encourage caution in mastering because it can generate audible distortion through consumer playback systems—and that distortion is generally not desired. Professionals are fully aware of this. But given the diversity of musical genres—many of which are not tied to the historical codes of perceived level—mainstream music or any sub-genre can legitimately pursue its own aesthetic choices.

In mastering, we aim to deliver music that fits genre codes while remaining competitive. True Peak alone never determines mastering quality. A successful mastering depends on a coherent set of processing decisions based on intention, experience, and context. With expertise, the mastering engineer improves perception while adapting to both the art and the market.

A master that “sounds loud” is not necessarily a bad master. It can enhance a mix and reinforce genre representation. Conversely, a master strictly following recommended maximum True Peak values is not necessarily better: this single criterion is clearly not sufficient.

In today’s society, most listeners use poor playback systems that cannot properly reproduce the qualities embedded in studio music. These systems are often incapable of handling True Peak levels beyond a certain threshold. In terms of everyday listening, we may need to change habits and finally invest in more qualitative setups.

However, vinyl’s resurgence—with continuously growing sales since the 2010s—seems to demonstrate renewed enthusiasm for this format. Vinyl, by nature, presents no True Peak issues because it is purely analog. Interestingly, vinyl also reflects a conscious and qualitative approach to listening.

LPCM vs DSD: how True Peak behaves

True Peak is intrinsically linked to LPCM encoding—it is, by definition, one of its major weaknesses. In the analog reconstruction of a signal from samples legitimately created within the digital scale, there will always be cases where successive high samples produce an analog waveform that is limited in amplitude. In practice, ideally, it could have been converted without distortion if the original signal had been reduced or better controlled.

As we have seen through examples of dynamic music and heavily compressed mastering, True Peak management will always remain a weak point of the LPCM model.

By contrast, in DSD, the True Peak problem does not exist. DSD is based on generating a 1-bit stream at a very high frequency: samples are created successively based on the position of the previously generated sample in a feedback logic, known as Delta-Sigma. As a result, intersample overshoots cannot occur in the same way as in LPCM. DSD can still suffer from overload phenomena, but these arise from very different mechanisms specific to the technology (modulator, filtering).

This section highlights the fundamental differences between the two digital encoding technologies, while reminding readers that LPCM remains the standard in music production—which is exactly why True Peak management remains a central topic.

Representation of the same waveform encoded using both methods. At the top: LPCM for CD-Audio (16-bit, 44.1 kHz). At the bottom: DSD on 1 bit (always the case), but at a sampling frequency 64× higher. Source: Wikipedia, LPCM-vs-DSD, by Paweł Zdziarski, CC BY 2.5.

Key points to remember: True Peaks levels in Mastering

- True Peak is a phenomenon specific to LPCM encoding, linked to analog signal reconstruction.

- True Peak values do not indicate perceived loudness (RMS or Integrated Loudness).

- Excessive True Peaks may lead to: clipping in DACs, increased distortion during lossy encoding and decoding.

- Industry thresholds (−1 dBTP, −2 dBTP) are recommendations, not mandatory rules.

- Some musical genres intentionally embrace high levels and distortion as part of their aesthetic.

- DSD encoding operates on a different principle (Delta-Sigma) and is not subject to True Peak.

- In mastering, True Peak management is always a balance between technical constraints and artistic choices.

Blog glossary: “True Peak levels”

LPCM: Linear Pulse Code Modulation is by far the most widely used encoding system in professional audio and hi-fi. It is often shortened to “PCM” (Pulse Code Modulation), but strictly speaking that is a simplification. “Linear” means samples are evenly spaced, which is not always the case in “PCM”. LPCM is therefore a subcategory of PCM. For example, at 44.1 kHz (CD-Audio), there are 44,100 samples per second, evenly spaced. LPCM converts analog sound into a sequence of samples at a defined sampling frequency (44.1 kHz, 88.2 kHz, 96 kHz, etc.). LPCM also enables digital processing through DAWs and CPUs (gain, EQ, compression, harmonic generation, etc.). The most common LPCM container format is .wav (Waveform Audio File Format, Microsoft & IBM), but .aiff/.aif (Apple) and .bwf (EBU) also exist.

RMS: Root Mean Square. A purely mathematical average representing the mean of a function’s values over time. In pro audio, the function is the waveform. RMS describes the arithmetic mean of waveform amplitude across the duration of the track. It is reasonably representative of perceived amplitude, since we cannot perceive the waveform’s instantaneous maximum values in complex signals like music.

Integrated Loudness: Measurement of a track’s loudness over its full duration. The algorithm accounts for the non-linearity of human hearing across frequencies and intensity. It is established by the ITU; first published in 2006 as ITU-R BS.1770. The algorithm is intended to evolve to improve loudness precision and potentially also True Peak measurement.

ITU: International Telecommunication Union, based in Geneva (Switzerland), a UN agency responsible for telecom and communication technology standards.

Full Scale: The digital scale expressed in dBFS. The maximum possible value is “0”, since all values in this scale are negative. Full Scale also refers to that maximum value, i.e., “0”.

The DAC market today: These links refer to consumer devices focused on DAC conversion (and sometimes preamplification), but DACs are also integrated into multi-function hi-fi systems such as integrated amplifiers or some players.

Lossy: Unlike lossless, lossy encoding compresses data and removes part of the audible information in exchange for reduced file size. The most common example is mp3, which, despite development ending in 2017 by Fraunhofer IIS, remains the most widely used lossy format.

Brickwall limiter: A processing tool used to increase loudness while preventing a signal from exceeding a user-defined digital threshold (the highest being 0 Full Scale). In 1994, Waves released the L1 plugin, which opened the chapter of the Loudness War—alongside CD-Audio technology introduced in 1982.

Plugin: A software module inserted within a host application called a DAW (Digital Audio Workstation) to process audio files (EQ, compression, levels, etc.).

EBU: European Broadcasting Union, based in Geneva. Building on ITU work since 2006 on loudness and True Peak, the EBU published EBU R128 in August 2010 (“Loudness Normalisation and permitted maximum level of Audio Signals”), implemented in 2012. The EBU updates recommendations in line with ITU BS.1770 versions; the latest EBU R128-5 is from November 2023.

Stereo: Most music releases are still stereo (two channels) since the comercialization of Stereo vinyl in 1958 ! However, in 2025, multichannel distribution beyond stereo exists and is growing just a little compared to the much spread use of Stereo systems. Common formats include 5.1 and 7.1. Distribution focuses mainly on immersive audio (object-based formats) and, to a lesser extent, on physical media (Blu-ray Audio, Pure Blu-ray Audio, SACD) and multichannel downloads. Regarding True Peak, apart from SACD (DSD/Delta-Sigma), all other multichannel formats require the same vigilance as stereo because they are encoded in LPCM. See “LPCM vs DSD: how True Peak behaves”.

Smartphone use: According to a Qobuz study in 2021, 72% of young people listen to music using only their smartphone.